Back to News

Back to News

November 8, 2024

Hunting With Bob One Last Time

Editors’ Note: The following column was authored by Jay Pinsky, Editor of Hunting Wire and appeared was published Nov. 4, 2024. Jay Pinsky is a retired U.S. Navy Chief Petty Officer, and wrote this column to honor his father, the late U.S. Army Sergeant First Class Robert “Bob” James Pinsky. It is republished here with permission from Hunting Wire to recognize the unique relationship the U.S. military shares with the firearm and ammunition industry.

Next Monday, America will honor our veterans formally. I suspect this industry doesn’t wait until then.

Celebrating America’s veterans began when our freedoms did.

For every American, it’s at least a patriotic holiday. For some, like me, it’s also deeply personal.

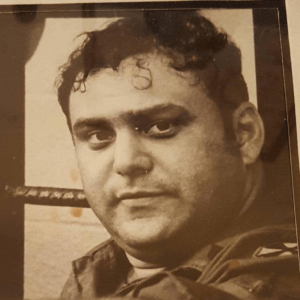

My veteran is my father, the late U.S. Army Sergeant First Class Robert “Bob” James Pinsky.

Dad was born on July 13, 1945, to Charles and Edith Pinsky, themselves immigrants from Russia. Bob grew up in Connecticut and later enlisted in the U.S. Army. After surviving Vietnam not once but three times hanging out of a UH-1 Huey as its crew chief and door gunner, he returned home to meet my mother, Martha Annette Marsh, while stationed at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. A few years later, I was honored to become his son. Then, he joined the U.S. Army’s elite 5th Special Forces Group and finished his military career at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, in 1985.

One would think that I, the editor of The Hunting Wire, might draw on some of my fondest hunting memories with my dad. I don’t have any. Hunting was never his thing, but being a good father was. Once I showed an interest in hunting, he made sure I had the right mentors to learn things he couldn’t teach me.

I spent plenty of boyhood time in the North Carolina pine straw chasing deer, rabbits, squirrels, and the occasional bear. I just didn’t do it with my dad. Most often, it was because he was deployed to God knows where doing God knows what. But even when he was home, no matter how much I asked, he wouldn’t go. Looking back, I think Vietnam showed him all the dying he never wanted to see, so any death, man or beast, was too much for him. I was confused by that as a boy, but as a man, I’ve learned to respect him for it.

My father passed away on June 9, 2016.

My dad was a wonderful father. I know and love God. I am a loyal husband and selfless father. I retired as a U.S. Navy Chief Petty Officer in 2012. I hold a Master of Science from Virginia Tech and continue serving our nation as my local American Legion commander.

I still hunt without him, until now.

Earlier in 2024, I decided to take my father on the hunt of a lifetime. The choices for such a hunt are endless for many, but not for me. While many fancy an elk, moose, or brown bear as the end-all-be-all beast of pursuit, I’m slightly different. The cliff-dwelling, rock-hopping, gravity-defying aoudad is mine.

Why?

I think it’s because of where they live and how hard they are to kill. They live on the sides of rock cliffs hundreds of feet tall and canyons hundreds, if not thousands of yards across. Just getting on eye-level with an aoudad from afar is a bucket list pursuit. Killing one is something else, especially when you factor in the fact that I’m as nimble as a rock and climb like a bowling ball. So, announcing to myself and the world that I’m going on an aoudad hunt is, at the very least, ambitious and could be, at worst, deadly.

I wanted to do it.

I’d like to tell you I’m a macho kind of guy, but I’m not. Honestly, I’m cautious and sometimes anxious. So, wanting to hunt an aoudad and doing it were two completely different things. Then, a few days after Memorial Day, I took a deep breath and reminded myself that I was the son of a Green Beret. I told myself, damn right, I was going to go kill an aoudad and show my dad that I could do anything.

So, I did.

A good attitude is helpful, but it won’t put down a 300-plus pound big-horned mass of muscle that is the aoudad. Finding an aoudad is hard. Getting within rifle range is even more complicated. Then, you still must hit one well and have it drop where you can get to it. And after all of that, God willing, you must go get it and bring it home without getting hurt or worse. The bottom line is that killing an aoudad is hard. It’s even harder with a bad rifle. So, I called the best custom rifle builder I know, Mark Banser, and asked him if he’d help. I added a small caveat, though.

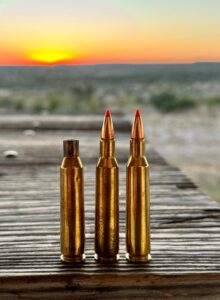

Mark, I want you to build me a rifle to honor my father and chamber it in 257 Roberts so I can call it “Bob.” I told him I wanted to go kill an aoudad with it and then auction that rifle off and donate every penny to The Green Beret Foundation to honor his legacy. Mark, himself a U.S. Army veteran was onboard immediately. Starting with a Winchester Model 70 rifle I already owned and a .25-caliber Douglas barrel I bought off GunBroker.Com, Mark added a Timney trigger, his own customized carbon-fiber stock painted by Custom Gun Coatings, and countless man hours of world-class gunsmithing to create a Green Beret Tribute Rifle.

As Mark continued to mold and craft the rifle, other industry partners learned about our project and jumped in to help. Hornady sent two cases of 117-grain SST ammo, one for hunting and the other for the auction, so fast I swear the ammo arrived before I finished the email asking for it. Fun fact: the 257 Roberts is a favorite of Hornady’s Seth Swerczek.

Then, Pelican donated a hard case for the auction, GunBroker.Com offered to host the auction pro bono and to top it all off – literally, world-class optics manufacturer Swarovski donated their top-of-the-line Z8i 1.7-13.3x42mm riflescope.

By the first week of October, Mark had sent me the finest rifle I had ever seen, partly because of his incredible skills and equally because of our industry’s world-class patriotic generosity. It was and is a rifle I could never afford, which is fitting to honor a priceless man.

Believe it or not, building the rifle was the easy part. Now I had to go kill an aoudad with it.

Enter Shane Jahn. Texan, husband, father, retired U.S. Border Patrol agent, gun writer, and aoudad guide. I learned about Shane during one of Andy Larsson’s annual Shot Show breakfast events a few years ago. We stayed in touch, and during last year’s Dallas Safari Club, Shane and his family had lunch with my wife, Wendy, and me. Shane’s the kind of man that makes you understand why people are willing to die to protect Texas. Noble, honest, kind, and generous, Shane is a good man. At worst, I figured Shane would ink a few stories for me at The Hunting Wire, and at best, I hoped we would become friends.

I told Shane about my dream to kill an aoudad. He didn’t flinch. Shane also likes to hunt cape buffalo with handguns, so there’s that. Shane worked on some contacts and got us exclusive access to a private ranch in West Texas with aoudad on it. Over Columbus Day weekend this year, I headed down to West Texas to hunt aoudad with Shane, my father, and the Green Beret rifle.

Before we stepped off to hunt, we checked the zero on the Banser 257 Roberts. I took three shots and made two holes about half an inch apart from each other and an inch high at 100 yards. Shane quipped, “Well, you won’t be able to use that rifle as your excuse for not getting your aoudad.”

Again, no pressure.

Hunting aoudad on nearly 40 square miles of the Chihuahuan Desert, the largest hot desert in North America, was precisely what I thought it would be – daunting. I’m not the only one to think that either. To borrow a quote from the television series Yellowstone – “Texas? You ever been? Then you don’t know. Everything in that place is trying to bite you, stick you or sting you. It’s 110 degrees in the shade.”

The Aoudad like heights and more personal space than a teenager. West Texas had plenty of both. We saw Aoudad from afar the first evening. The 257 Roberts is a 500-yard aoudad gun at best, and by the end of the first day of hunting, I wondered if its reach would be far enough.

We went as far as the UTV would safely take us, which varied from place to place and day to day. Then we hiked up and down loose west Texas desert rock looking for aoudad. Despite it being mid-October, the Texas heat still topped 95 degrees daily, so we used the UTV as much as we could. It helped, but what helped more were the LaCrosse Ursas laced to my feet. Like I said, I’m not the most agile guy, but those boots, purpose-built for hunting just like this made me think I was. I stepped on and through anything I wanted to, sometimes at angles I shouldn’t be at, and not once did I ever wonder about my footing. Rocks, cactus, briars, thorns, and other gotcha stuff never phased my feet. Now, my hands, legs, and, on occasion, my behind were another story.

The truth is that aoudad hunting is simple. You glass. You climb to glass more. Then you climb higher. Glass more. Hike more. Glass. Climb down. Glass. Ask yourself where the hell the aoudad are, then glass some more. I’ve never spent more time behind a pair of binoculars, so when I tell you Swarovski’s 8×42 EL Rangefinder binos are good, I say so with vigor.

By day 2, I was finding aoudad as well as Shane, and sometimes before him. Unfortunately, they were either ewes, kids, or young rams, which were well worth seeing but not mature enough to shoot – especially on this hunt. By now, 400 yards seemed like a chip shot compared to most aoudad sightings. At dusk on day 2, I spotted a shooter ram, but we couldn’t close the 2200-yard gap between us by the end of the shooting light. I went to bed thinking seeing one that big was as good as it would get.

God had other plans.

Our ranch-hand scouts were correct with their intel, but none of the rams we saw were shooters, and this wasn’t a sight-seeing trip. The next morning, Shane and I decided to head to the other end of the property to find a shooter. All we saw was more of Texas, and when we squinted, Mexico.

Throughout our hunt, between lessons on aoudad behavior and habits, Shane and I talked about being sons and fathers. It’s a common bond amongst many men and the best bond with the right men. Shane was both.

Sometimes, I spoke with regret about what I wish I could have done or said to my dad when he was alive. My head dropped at the thought that I was a disappointment to my father. Shane would have none of it and reminded me that all men have these thoughts, and it didn’t make any man who tried to be more failures. Shane reminded me that all men want to be better than they are, but the good men, they do something about it. Like not just wanting to hunt an aoudad but doing it. It was then that I found peace with losing my dad and being his son.

It was the moment God was waiting on too.

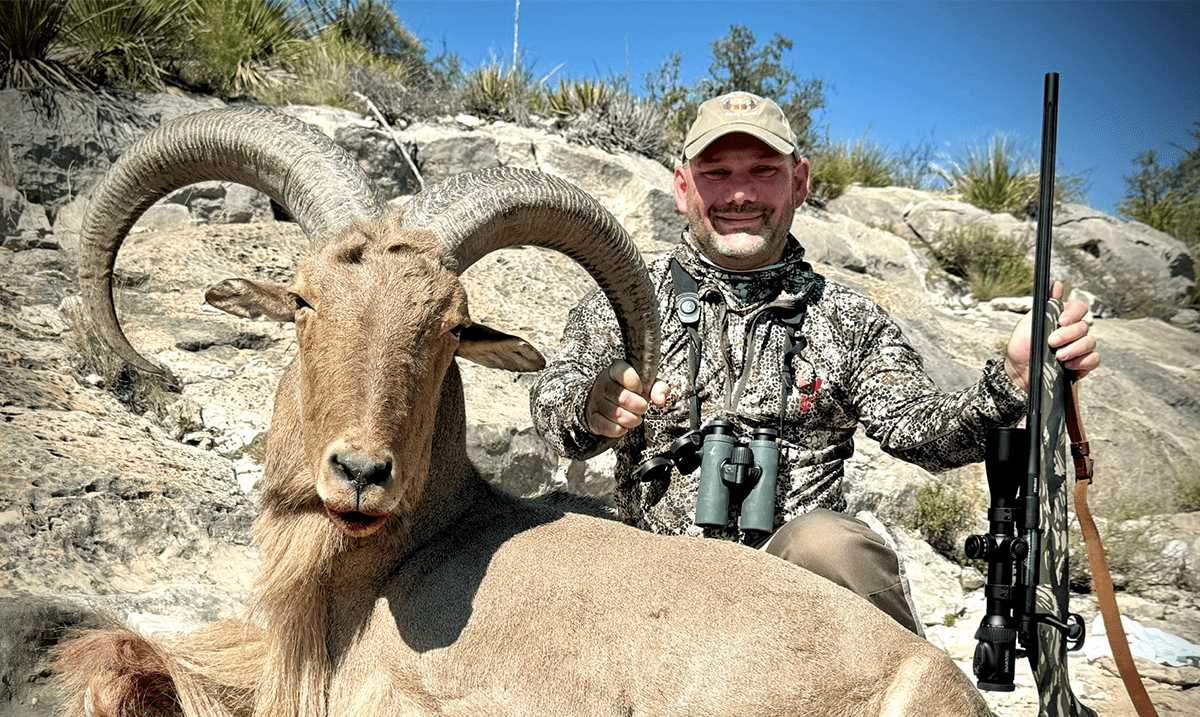

A few minutes after I found peace, a trophy aoudad stepped out at a mere 129 yards by a watering hole as if following a script written by God himself. Within seconds, I squared up the rifle on a pair of shooting sticks, found the center shoulder, and squeezed the trigger. The aoudad dropped. I cycled my bolt and stayed on the gun, ready to follow up with a second shot. Then, he rolled from right to left and fell down the cliff another 20 yards or so. After one magnificent death kick, he lay motionless. There would be no second shot.

Nice shot, Shane said. I smiled and then fell apart emotionally. My body shook, and my stomach tied itself into knots as all the adrenaline surged out of my body. Shane stuck out his hand, but I hugged him instead. That’s when I finally understood that honoring my father was never about killing an aoudad. It was about having a dream, any dream, and making it come true. So, I did.

I love you, dad. Happy Veteran’s Day.

Your son, Chief Petty Officer James G. Pinsky

Categories: BP Item, Featured, Hunting, Top Stories